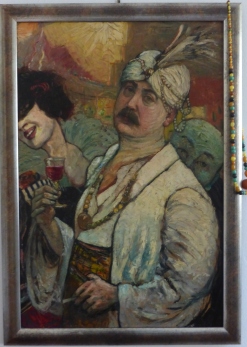

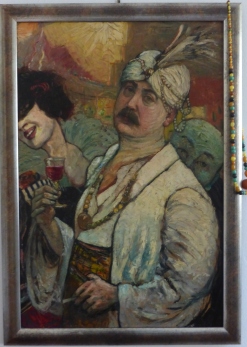

Hanns Diehl, Self-portrait with Turban, ca. 1925.

When Diehl’s self-portrait in a turban–apparently depicting him at Carnival time–was exhibited at Vienna’s Galerie Hieke in 1993, a critic wrote that it revealed the artist’s ability to recognize his own character flaws, namely vanity and self-aggrandizement. (”Er schreckte auch vor Selbstpersiflage nicht zurück. Sein ‘Selbstbildnis mit Turban’…wirkt wie ein Bekenntnis zu den eigenen Schwächen, wie Eitelkeit und Selbstüberschätzung.” Rüdiger Engerth, ”Mit scharfen Buntstiften,” Kurier, 28 January 1993, p. 14.) This analysis may overestimate Diehl’s own self-awareness, but it is an accurate characterization of some aspects of the artist’s personality. When I first saw the work, I was intrigued primarily by its artistic merits, as the painting represents, to my mind, Diehl’s most assured coloristic style, with its bold colored outlines and thick impasto paint. But as I have continued digging deeper into his life and work, it appears that the work does capture something of his eccentric and contradictory character.

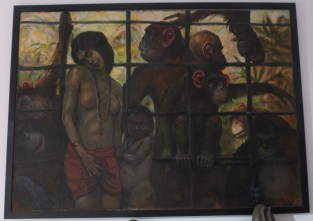

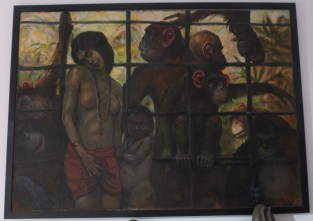

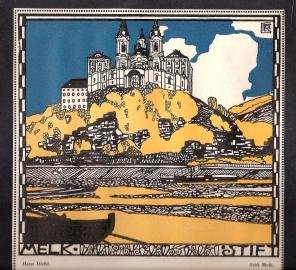

One of Diehl’s designs for stained glass.

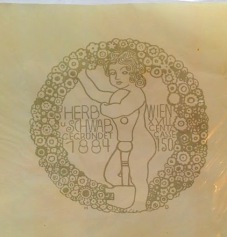

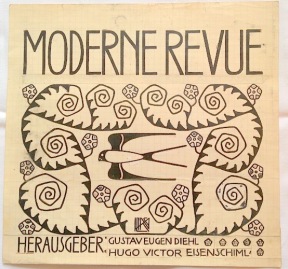

When Diehl moved to Vienna in 1906, he was meant to take over the running of the Herb & Schwab glass factory owned by his uncle. He did make designs for the company’s glass windows, at the same time becoming active in the city’s art world. He created ex-libris for clients, submitted prints to magazine publications, painted in every genre and drew whatever struck his fancy. He was still experimenting in a variety of styles, imitating the popular motifs of, among others, Jozef

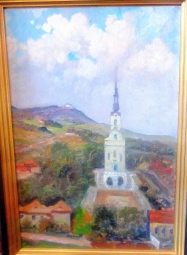

Hanns Diehl, Landscape in Schnackendorf, ca. 1910.

Israëls (1824–1911), Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) and Max Klinger (1857–1920). He was intent on being an academic artist in the mode of his hero Wilhelm Trübner, but had not chosen to specialize in any medium or genre. He was still employed at Herb & Schwab when World War I began in 1914.

Still a German citizen, Diehl immediately volunteered and was assigned to the War Ministry in Munich as a Russian translator. As translator and then as a war artist,

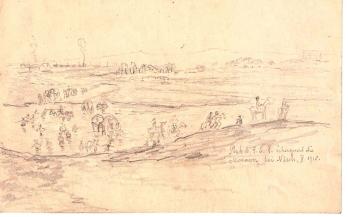

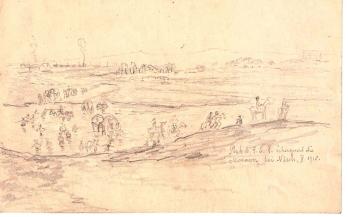

Hanns Diehl, Stab d. F.B.R. überquert die Morawa bei Nisch, X. 1918.

he saw action on the fronts in France and in Serbia. He was greatly traumatized by what he experienced on the front; he wrote “The unheard of terror of this war I saw and experienced in France and Serbia; an enduring impression of unlimited and completely inhumane barbarity”.

Scene on the battlefield, 1918

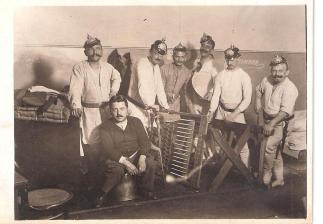

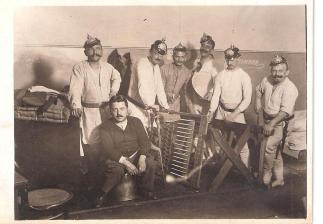

He nonetheless seemed, from all accounts and from the photos he sent home to his wife, to feel a sense of camaraderie with his fellow soldiers.

Diehl (seated), with his army comrades in World War I.

In 1916, apparently on leave from service, he returned to Vienna to marry Anna Pangratz.

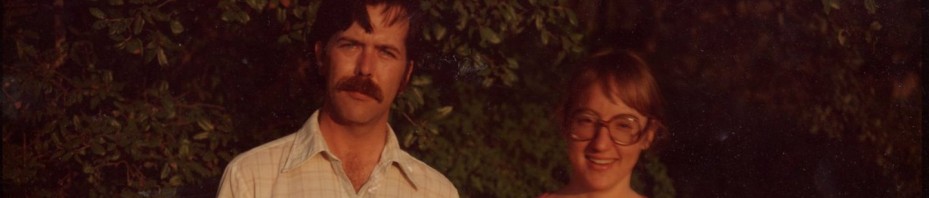

Hanns and Anna Diehl, 1916.

The story of their first years offer telling insights into Hanns’ character. At about the time of their marriage, Hanns made it clear that he had no desire to take over the glass business; he wanted to be a professional artist, and possessed little business acumen (he said he did not want to negotiate with the workers or the unions). Anna, who was a capable businesswoman, had given up a good position at the Handelskammer (the Chamber of Commerce) because she thought she was marrying the director of a company. When Diehl rejected this position, Anna went back to work as the supervisor of the correspondence department of the Anker-Brot bakery firm, a position she held for 25 years. Hanns was now free to pursue his career solely as an artist. Hanns and Anna had one daughter, Ingeborg, born in 1917 (Ingeborg was the mother of both Heidi and Nora).

——————————————————–

AN ASIDE: Anna was not the only woman at the time who ended up supporting her artist husband; the wife of the futurist writer Paul Scheerbart comes to mind. Her granddaughters remembered their mother saying that their grandmother would proudly say ”I work like a man, and I get paid like a man.” Anna would have made a good subject for books like Ulrike Halbe-Bauer’s Die Frauen der Künstler, which deals with this particularly category of women in the 19th and 20th centuries.

——————————————————–

Hanns Diehl outdoors with peasant models, ca. 1920.

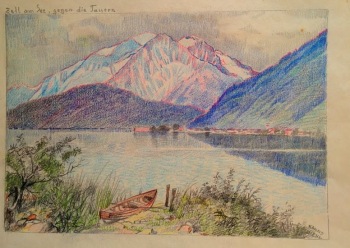

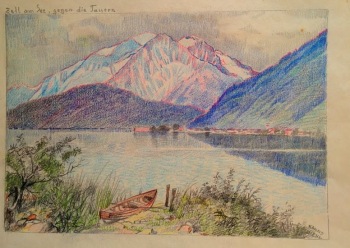

The 1920s and early 1930s were Diehl’s busiest and most productive years, although he never had many patrons. He travelled throughout Austria and to the Croatian coast, making magnificent color sketches and watercolors everywhere he went.

”Zell am See, gegen die Tauern,” ca. 1927.

Istrian Coast, watercolor, ca. 1930.

His drawings are especially strong, with an excellent sense of perspectival depth and shading. This facility would never leave him, and his sketches–hundreds of them remain in the family’s collections–reveal a spontaneity and exacting eye for detail at the same time.

In the Schloss garden at Wetzdorf, 1933.

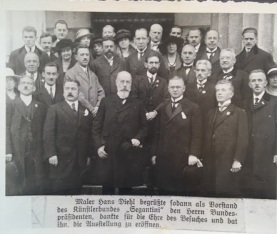

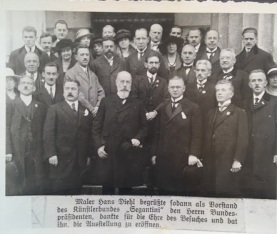

In 1921, as a response to what he saw as the onslaught of modernist artistic directions , he established with several other artists the

Diehl is in the front row left.

”Künstlerbund Segantini.” He served as its director for the remainder of its lifespan, until the onset of World War II. This artist’s organization was committed to a traditional idea of painting, emulating the Austrian-Swiss painter of symbolic Alpine landscapes, Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899). This romantic Germanic style appealed to Diehl’s emotional instincts, but his work never copied Segantini’s motifs. Critics of the time speak of his work as showing an individual streak within traditional painterly parameters—that he always went his “own way” —and by this time, Diehl was indeed formulating his own stylistic preferences. One critic of the first Segantini-Bund exhibition described his works admiringly as depicting “architectonic fantasies”(“Ausstellung des Künstlerbundes ‘Segantini’,” ”Illustriertes Wiener Extrablatt”, vol. 50, nr. 124, 7. May 1921, p. 1). The other members of the Segantini-Bund varied in ability and styles, from the treacly winter romps of Gustav Prucha (1875-1952) to the quite polished post-impressionist works of Maria Egner (1850-1940) and Lilly Hofmann-Stein (1884-1961).

Diehl landscape at an exhibition of the Segantini-Bund, at the Burgtor Wachhaus, ca. 1930.

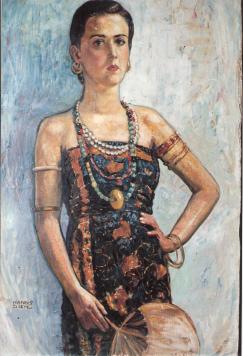

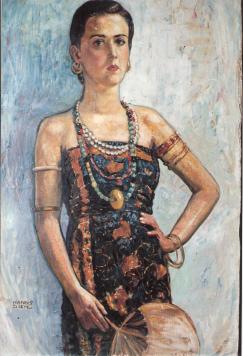

By the mid-1920s, Diehl’s work began to take several variant turns. On the one hand were his oils, which now reveal a firm linear outline, with a near-impasto use of thick color. This style would be incorporated into most of his late oil paintings.

Still life with flowers and bananas, 1923.

Portrait of Ingeborg, ca. 1935.

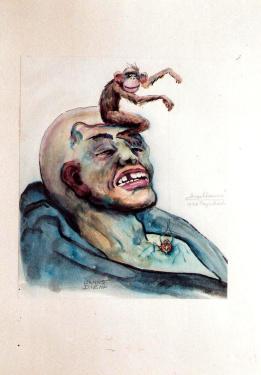

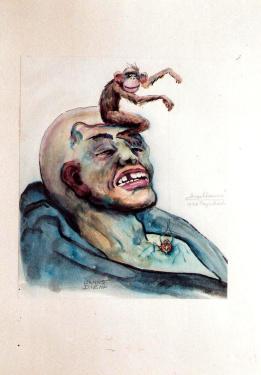

The other direction that began to surface in the late 1920s exemplifies Diehl’s contradictory nature. Despite his anti-modernist assertions, he began to create, apparently for private amusement, a series of eccentric, caricature-like watercolors that reveal a knowledge of works by such modern figures as Emil Nolde and Alfred Kubin. These often satirical commentaries are unlike any of his other, more formal works, and are described by later critics as revealing both a scurrilous sentiment and a debt to German Expressionism. These sometimes anguished images are the pieces that have endured, and are of greatest interest to contemporary audiences, who see in them a psychological reflection of the time between the wars in Vienna.

Some of these works–most of them in watercolor–also seem to relate to some personal situation in Diehl’s life–perhaps illness or a reaction to contemporary politics–but they demonstrate another side of his creative mind. These were apparently meant for private amusement and not for public exhibition.

A heart under examination, 1934.

Ein Angsttraum (A NIghtmare), 1934.

The Sword Dancer, ca. 1930.

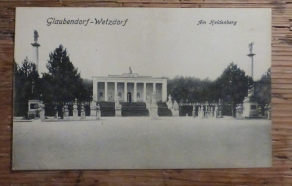

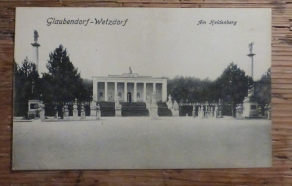

Schloss Wetzdorf, ca. 1932.

The painting above of Schloss Wetzdorf alludes to another of Diehl’s many sides. Some time in the 1920s, he became acquainted with the eccentric owners of this country estate (site of Heldenberg, a military  memorial where the famous Austrian general Joseph Radetzky von Radetz–he of Strauss’s Radetzky-March–was buried). Anton Fichtl, the

memorial where the famous Austrian general Joseph Radetzky von Radetz–he of Strauss’s Radetzky-March–was buried). Anton Fichtl, the

Diehl’s portrait of Anton Fichtl, 1921.

Schloss’s owner, and Diehl must have shared political attitudes and a penchant for partying. According to the granddaughters, Diehl’s frequent visits to Schloss Wetzdorf were a source of friction between Hanns and his wife, and may have in the end led to her decision to divorce him. By the 1940s, she had had enough. A series of life drawings from this time done at Wetzdorf may give some indication of the activities that Diehl and the rest of the company enjoyed at the Schloss.

Nude drawing, ca. 1933.

Life study, ca. 1932.

Still, these years were also filled with lovely drawings for his daughter and wife, and, later, sweet images for his granddaughter Heidi. The two paintings of sleeping girls are sides of a room panel that Diehl painted in 1929, and the booklet a story about their family dog.

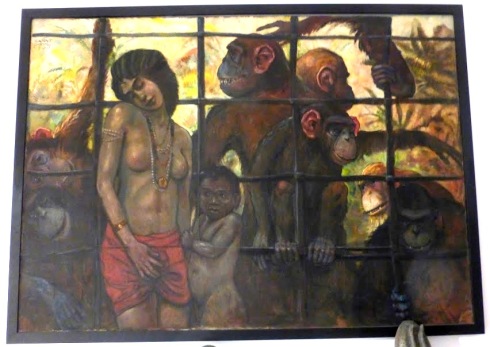

Ever short of patrons and often without enough money to buy materials, Diehl did take on students, and at times offered drawing classes. In one of his most cryptic and intriguing works, Affenballade (Ballad of the Apes), he created a grid of bars that are painted along the lines of the Hessian sacks he used as a canvas. Mention of this amazing work brings us full circle, as it was this painting, now hanging in the apartment where we are staying, that first aroused my interest in Hanns Diehl’s art. (See part I of this saga.)

Finally, we come to that point in any discussion of German/Austrian art of the 20th century that requires suspending knowledge of what was to come. Here I am just going to repeat what I have written in our Wikipedia entry for Hanns Diehl (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanns_Diehl):

Hanns Diehl was, like so many of his contemporaries, a romantic nationalist—a German who had become a naturalized Austrian citizen in 1926, at a time when notions of national identity were particularly urgent, after the defeat in World War I and the fear of Soviet-style Communism engulfing the countries. Artists as diverse as Nolde and Lyonel Feininger initially praised Hitler and Mussolini’s efforts. Diehl became a member of the National Socialist Party even before the Anschluss in 1938—a decision that would come to haunt him after World War II. When the Nazis did take over Austria, Diehl naively saw the regime as offering job opportunities. He became one of the directors of the Gemeinschaft bildender Künstler, the Society of Visual Artists, and submitted designs for the Party’s official publications and events. He was to be bitterly disappointed that the regime was to exclude so many artists from its official exhibitions, writing a letter of complaint to the Party officials expressing his dismay at this lack of ” National Socialist collegiality.” This complete lack of understanding of the Nazi Party’s political goals is indicative of so many cultural figures of the time. Diehl never expressed any anti-Semitic sentiment, and after the War, when he was briefly imprisoned, it was the testimony of a Jewish neighbor that assured his release.

The real reasons for his arrest in 1946 have been muddied, but appear to have more to do with a squabble over studio space that caused Diehl to be turned in to the authorities as a Nazi party member. Because of the chaos of the judicial system immediately after the war, he remained in remand “under investigation” for 8 months. He was never brought to trial, convicted of any offense, or even formally charged with any offense. The

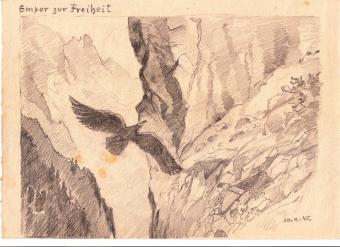

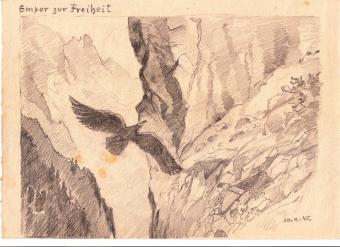

”Schicksalwendungen” (Changes of fate), drawn when Diehl was arrested, 1945.

situation broke him nonetheless. Although divorced by Anna by this time, he still went to live in her house. On December 22, 1946, both she and Hanns died of asphyxiation from a faulty gas heater. It is still unclear if their deaths were an accident or suicide.

Perhaps because of his close ties to the Nazi Party, Diehl was forgotten, even as other members of the Segantini-Bund gained some recognition. In 1963, his family organized an exhibition of his work at the Österreichische Staatsdruckerei, at which time the art critic of the Wiener Zeitung wrote that he was a painter who had been unfairly forgotten.Another exhibition at the Galerie Hieke in 1993 praised his watercolors and personal paintings of the 1920s as his best work, labelling him as an artist “between tradition and eccentricity.”

Hanns Diehl, ”Empor zur Freiheit” (Arise to Freedom), 1945.

Tags: Artists and Nazism, German art, Hanns Diehl, Viennese art

Some of the displays of the over 60,000 objects on the Museum’s four floors make it look like an auction house, but even these sections have explanatory labels.

Some of the displays of the over 60,000 objects on the Museum’s four floors make it look like an auction house, but even these sections have explanatory labels.

Have I already explained the differences between Apotheke, Drogerie, and Parfumerie? An Apotheke is where you go for medications, a Drogerie is for cosmetics and hair color and those kind of things, although the big chain BIPA has household cleaning stuff and photo machines, just like a Walgreen’s.

Have I already explained the differences between Apotheke, Drogerie, and Parfumerie? An Apotheke is where you go for medications, a Drogerie is for cosmetics and hair color and those kind of things, although the big chain BIPA has household cleaning stuff and photo machines, just like a Walgreen’s. several kinds. The best one to get is Weizen Mehl Universal–which is the same as our All-Purpose flour. If you’re going to be here for long and will be wanting to make American recipes, be sure to bring your cup measures and teaspoons/tablespoons. Measurements here are done by scales.

several kinds. The best one to get is Weizen Mehl Universal–which is the same as our All-Purpose flour. If you’re going to be here for long and will be wanting to make American recipes, be sure to bring your cup measures and teaspoons/tablespoons. Measurements here are done by scales.

memorial where the famous Austrian general Joseph Radetzky von Radetz–he of Strauss’s Radetzky-March–was buried). Anton Fichtl, the

memorial where the famous Austrian general Joseph Radetzky von Radetz–he of Strauss’s Radetzky-March–was buried). Anton Fichtl, the

![burgtheater_1900[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/burgtheater_19001.jpg?w=300&h=197)

![volksoper_postcard[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/volksoper_postcard1.jpg?w=300&h=186)

![raimundtheater_postcard[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/raimundtheater_postcard13.jpg?w=300&h=193)

Grand Hotel, ca. 1900.

Grand Hotel, ca. 1900.

![hotelbristol_1916[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/hotelbristol_19161.jpg?w=275&h=176)

![hotelsacher_ca1890[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/hotelsacher_ca18901.jpg?w=300&h=190)

![erzherzogkarlhotel_1900[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/erzherzogkarlhotel_19001.jpg?w=225&h=146)

![hoteldefrance_1905[1]](https://esauboeck.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/hoteldefrance_19051.jpg?w=300&h=192)

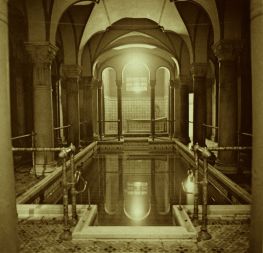

Central Bad, ca. 1910

Central Bad, ca. 1910

house revealed that, along with hundreds of paintings and a trunk full of documents, they even still had his palette! I took some photos of the paintings out in the country, and then brought in to Heidi’s apartment the rest of the papers. I have now gone through a sizable chunk of this material, and have decided that a blog entry is an appropriate first step. We have already begun a Wikipedia entry, but it is not yet complete enough to be submitted; by writing this blog entry first, we’ll have a reference to cite in the literature section that will be acceptable to the Wikipedia administration. There are still gaps in what we know about him; all three of us have been hampered by the fact that despite a number of letters in his records, Diehl wrote in such difficult ”Alte Schrift”–old-style German handwriting–that none of us can read them easily! At this stage, I am going to present here what information I have, along with comments about his art, and interject throughout questions that I still have about his life and his works. Some of these may never be answerable, or I will have to speculate on possible motives or sequences of events.

house revealed that, along with hundreds of paintings and a trunk full of documents, they even still had his palette! I took some photos of the paintings out in the country, and then brought in to Heidi’s apartment the rest of the papers. I have now gone through a sizable chunk of this material, and have decided that a blog entry is an appropriate first step. We have already begun a Wikipedia entry, but it is not yet complete enough to be submitted; by writing this blog entry first, we’ll have a reference to cite in the literature section that will be acceptable to the Wikipedia administration. There are still gaps in what we know about him; all three of us have been hampered by the fact that despite a number of letters in his records, Diehl wrote in such difficult ”Alte Schrift”–old-style German handwriting–that none of us can read them easily! At this stage, I am going to present here what information I have, along with comments about his art, and interject throughout questions that I still have about his life and his works. Some of these may never be answerable, or I will have to speculate on possible motives or sequences of events.

drawing. Some of his later paintings relate to his Russian life, and during World War I, he was able to use his Russian language abilities to serve as a translator.

drawing. Some of his later paintings relate to his Russian life, and during World War I, he was able to use his Russian language abilities to serve as a translator.

ambitions.

ambitions. involved in the art publishing world of Berlin into the 1930s. Gustav was definitely more modern than Hanns, who had a reactionary streak even at this early date. Do you know anything about their relationship, or why Hanns would not have gone to Berlin, or been part of Gustav’s artistic circles?

involved in the art publishing world of Berlin into the 1930s. Gustav was definitely more modern than Hanns, who had a reactionary streak even at this early date. Do you know anything about their relationship, or why Hanns would not have gone to Berlin, or been part of Gustav’s artistic circles?